Martin Luther Biography

Luther’s Early Years

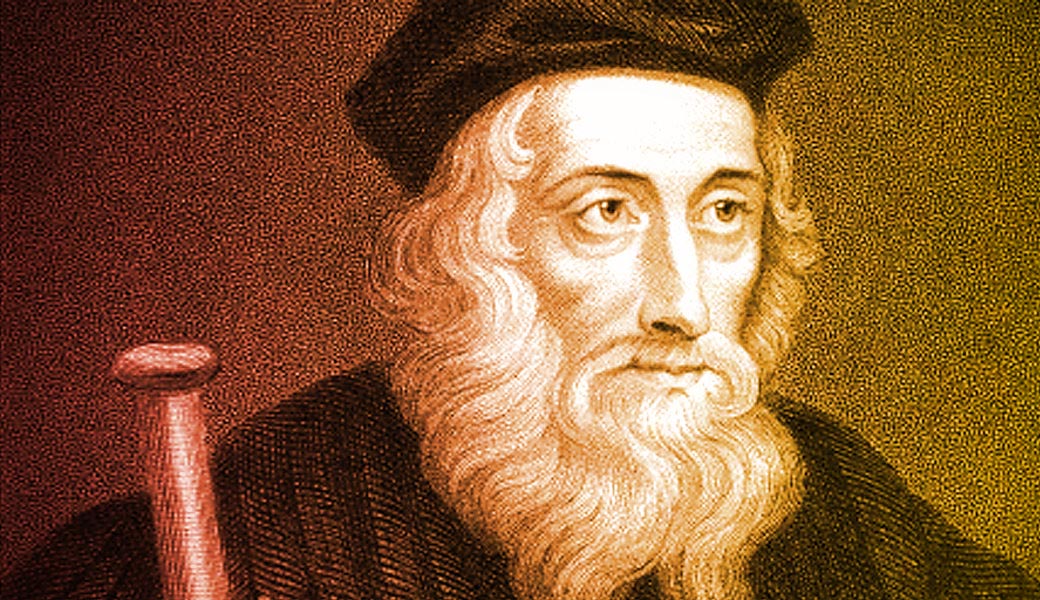

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was born on November 10, 1483 in the small town of Eisleben in the province of Saxony. This was part of the Roman Empire, predecessor to modern day Germany. His father, Hans, spent much of his life working in copper mining, while his mother, Margarethe, was a typical hardworking housewife. Young Martin was baptized on the feast of Saint Martin of Tours, and thus he was named after the famous Christian. He was the eldest son in his family, but not much is known about his brothers and sisters. Hans Luther desired for his son to become a lawyer and sent him to schools in Mansfeld, Magdeburg, and Eisenach, where he received a standard late medieval education. Martin was not particularly fond of any of these places.

Becoming a Monk

Martin then moved on to the University of Erfurt to study law. This is where we begin to see real signs of frustration. His study of the ancient philosophers and medieval academics was unable to satisfy his growing desire for truth. Of particular importance to Luther was the issue of assurance: knowing where one stood before God. His desire for such assurance was already drawing him to the scriptures, but a seminal event was to push him further in that direction. While riding at night in a thunderstorm, a lightning bolt struck nearby and Luther famously cried out, “Help, Saint Anne! I will become a monk!” He later attributed this statement to his fear of divine judgment, believing himself to be steeped in sin. Two weeks later, he became an Augustinian monk at the monastery in Erfurt, a decision that highly upset his father.

Luther’s Theological Breakthrough

Luther may have hoped that monastic life would bring him some internal peace, but it did nothing of the sort. Rather, he found himself working harder and harder to please God and becoming rather obsessive about confession. His superior, Johann von Staupitz, directed him toward teaching, sending him to the new University of Wittenberg to focus on theology. This proved to be highly beneficial for Luther. His entry into the priesthood had caused him a further crisis of conscience when he felt unworthy to conduct the Mass. However, in teaching through books of the Bible, Luther himself was to learn a great deal. Of particular importance were his lectures on the books of Romans, Galatians, and Hebrews, which led him to a new understanding of how man is made righteous before God. It was during this time that Luther became convinced that man is justified by grace through faith alone, and that God himself declared the sinner to be righteous based on the work of Christ. In this doctrine, Luther had what he craved: assurance of salvation.

Luther and Indulgences

Martin Luther with his Bible

Despite his changing understanding of the scriptures, it is important to note that Luther did not immediately leave behind his monastic life. Instead, he continued on in teaching and clerical ministry just as he had previously, although he had greater spiritual peace. Yet, controversy soon arose due to the selling of indulgences within the empire. These were essentially certificates carrying the blessing of the Pope, which promised that the bearer would be released from a certain amount of penance, either in this present life or in Purgatory. These particular indulgences were given to those who made donations to build the new St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Luther became concerned that the indulgence sellers were ignoring the need for personal repentance. Thus, he composed a list of 95 theses (that is, points for argument) that he intended to debate with his fellow academics, and sent it to one of his superiors, the Archbishop of Mainz. The public was quickly informed of Luther’s arguments when they were translated from Latin, the scholarly language of the day, into German, the language of the common people. Although he did not question the authority of the pope in this document, it was clear that Luther’s understanding of justification and repentance were somewhat different from those that had been taught by many medieval theologians.

Moving Farther from Rome

The controversy surrounding Luther quickly grew, with some announcing their support but most of the Church hierarchy in opposition. This was a difficult time for Martin Luther as he had to decide between maintaining his unity with the Church and clinging to what he felt was the correct understanding of scripture. At first, he offered to remain silent if his opponents would do the same. However, he was eventually drawn into two different public disputations. The first involved his own monastic order – the Augustinians – and took place in the city of Heidelberg. Here Luther laid out some of his foundational beliefs about the nature of Christian theology, which were to pull him farther from Rome. In 1519, he traveled to the city of Leipzig, where his Wittenberg colleague Andreas Karlstadt was to debate the academic Johann Eck on the topic of free will. As it was clear that Eck really wished to attack Luther, Martin did end up agreeing to debate with him. During their disputation, Luther acknowledged his belief that scripture was the ultimate authority on issues of doctrine, and that Church councils and popes were capable of error. With this admission, Luther had taken another step away from Rome.

Luther’s Showdown at Worms

After their debate, Eck continued to press the case against Luther to those in Rome, and the following year, Pope Leo X issued a papal bull (edict) demanding that Luther retract many of his statements or be excommunicated. Surrounded by his university colleagues, Luther publicly burned the bull. The pope then followed through with the excommunication, and Luther was called to appear before Emperor Charles V at the imperial diet, which was meeting that year in Worms. (A “diet” was an assembly of the most important officials within the empire, and its edicts carried the force of law.) Although he was given a promise of safe conduct, Luther feared that this appearance may lead to his death under accusation of heresy. Nevertheless, he went to Worms, where he was once again called upon to recant what he had written. After some hesitation, Luther finally said the following:

“Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me. Amen.”[1]

Once again, we see how concerned Luther was with the issue of spiritual truth, and how he considered his assurance from God more important even than his physical life.

Luther’s Exile at Wartburg Castle

Martin Luther

Even as he was allowed to leave the city of Worms, there was a high probability that Luther would be seized and put to death. Instead, he was taken captive by men working for the ruler of his home region of Saxony, Elector Frederick the Wise. The Diet of Worms had determined that Luther’s writings were heretical, banned them, and authorized his arrest. As a result, Frederick arranged for Luther to be hidden securely in Wartburg Castle, which lay within Frederick’s own electorate of Saxony.

Martin spent about a year there and put his time to good use, not only writing numerous letters and pamphlets, but undertaking what was to be among the most important works of his life: the translation of the New Testament into German. In actuality, there was not one standard form of the German language in the 16th century, but Luther’s translation would prove so influential that it helped to standardize German as we know it today.

In this endeavor, Luther received help from his friend and fellow Wittenberg professor, Philipp Melanchthon. It was the young Melanchthon who was left in charge of the reforming work in Wittenberg while Luther was away, and it proved to be a tumultuous time. Their early ally, Karlstadt, had adopted a more radical set of theological views, and there were soon others like him. This led to serious discord in the city and beyond.

Luther’s Return to Wittenberg

In March of 1522, Luther made his return to Wittenberg out of concern for the problems that had arisen in his absence. Despite the obvious risks to Luther’s life as a result of being declared a heretic, he received the tacit support of Elector Frederick the Wise, who permitted the Reformation to continue within Saxony. Luther’s first task was to preach a series of sermons correcting some of the errors that had taken hold while he was away. Of particular concern to Luther was respect for authority and the ending of civil discord, and this was to prove very significant when the German peasant class started to demand greater political and economic rights. Luther criticized much of the violence that occurred, at one point in 1525 coming down particularly hard on the peasants. However, he did care about the common man: he simply did not believe rebellion was the answer to society’s problems.

Formulating the Reformation

Between 1520 and 1525, there were many changes in Wittenberg. Philipp Melanchthon published the first Protestant work of systematic theology, Commonplaces (Loci Communes). This work reflected much of Luther’s own thinking. Luther himself had published three important books just before appearing at the Diet of Worms: The Freedom of the Christian, The Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and his Letter to the German Nobility. Already, the ideas that were to drive the Lutheran Reformation were being codified. The Mass took on a very different form and was eventually abolished altogether as the standard of worship. Luther and his supporters also promoted the end of clerical celibacy and monastic vows, which would lead to the next major development in Luther’s life.

Luther’s Surprising Marriage

Martin Luther and his wife, Katharine Von Bora

As the ideas of the Reformation continued to spread, many men and women left the monastic life behind and sought to be married. It fell to Luther to arrange marriages for a dozen nuns who escaped to Wittenberg. He soon found husbands for all but one, a woman named Katharina von Bora. She eventually insisted that she would only be married to Luther or his friend and fellow theologian, Nicholaus von Amsdorf. Although he supported clerical marriage in principle, Luther at first rejected the idea of being married himself, fearing that he might be put to death, and in any case believing that the Reformation needed his full attention. In time, however, events led him to change his mind, and the former monk and former nun shocked everyone with the news of their private wedding service on June 13, 1525. A public ceremony was held later in the month. Some of Luther’s colleagues, including Melanchthon, feared that he had made a reckless decision that would attract scorn, but it turned out to be a good match, and Luther’s first son, Hans, was born within the year.

A War of Words

In the same year that he was married, Luther was engaged in a high-level academic battle with the most respected Catholic scholar of the day, Desiderius Erasmus. Although he was more of a public intellectual than a theologian, Erasmus had been under pressure for some time to make clear his opposition to Luther’s ideas. He found a point of disagreement on the issue of free will, and in 1524, Erasmus published the rather short Diatribe on the Freedom of the Will (De Libero Arbitrio). His main argument was that, while the grace of God was necessary for salvation, man still maintained some power to believe or not believe. Luther saw things in terms of flesh vs. spirit, believing that a person still trapped in sin is incapable of moving toward God of their own accord. He published a much longer rejoinder, The Bondage of the Will (De Servo Arbitrio).

This dispute proved influential more on account of the participants than the particular doctrinal ideas put forward, but it was clearly an important moment for Luther. Before his death, he listed this book as one of the few that deserved to survive after he was gone. Although the publication of this work may have pushed away Erasmus, it shows once again Luther’s continual drive for truth, even if it is hard for some people to hear.

Luther’s Hymn Writing

In addition to being a theologian, Martin Luther is also known as a musician. The many hymns he composed in the German language were a result of his concern that average people in the pews would understand the scriptural truths being put forward by the Reformation. He worked with his friends to create hymn books that could be used in all the churches. By far the most famous tune composed by Luther himself is “A Mighty Fortress is our God” (“Ein Feste Burg ist unser Gott”), but he left behind a vast wealth of hymns, many of which had an influence on the history of German music, particularly Johann Sebastian Bach. However, it was the practical aspect of getting congregants to connect with sound theology that was at the heart of Luther’s musical work.

The Augsburg Confession

In 1530, the emperor called another diet, this time in the city of Augsburg. Protestants were invited to attend the diet and present their theological views for the emperor’s consideration. Luther himself was unable to attend, as he was still under an imperial ban due to the Diet of Worms, and was thus restricted to Saxony, where he had the protection of the elector. However, he met with some of the other Reformers beforehand to discuss what they would say. A doctrinal confession was drawn up, with Philipp Melanchthon as the main author. It was read before the diet, but they did not succeed in swaying the emperor to the Protestant cause. As a result, the various cities and provinces that supported the statement – which came to be known as the Augsburg Confession – created a military alliance that provided further security for the Reformation ideas to spread. Although Luther himself was not an author of the Augsburg Confession, it has been the main confessional document for Lutheranism down to the present day.

Luther’s Relations with Swiss Reformers

While the Reformation had begun in Saxony, it quickly took root in other areas. One such place was the Swiss Confederation, which roughly lines up with modern day Switzerland. Here men such as Ulrich Zwingli developed their own ideas about how the Church should operate. There were a number of theological differences between the German and Swiss Reformers, but the one that proved to be particularly important involved the Lord’s Supper. Although Luther broke from Catholic tradition in his view of this sacrament, he did not go so far as Zwingli in adopting a largely symbolic view of what was taking place. A meeting between the two groups in 1529 produced an agreement on the fourteen Marburg Articles, but Luther and Zwingli were unable to come to terms regarding the Lord’s Supper.

This is another example of how Luther valued doctrinal truth above all else, for in pure political terms, it would have been to the advantage of the Protestants to stick together as closely as possible. Yet, Luther felt the issue so important that he could not compromise, and as a result, his relations with the Swiss Reformers were always strained. Even so, Luther’s writings would have a major influence on John Calvin, who in the next few decades became arguably the greatest theologian of the Swiss Reformation.

Luther’s Family Life

Despite the many difficulties he faced in his life, Luther’s home was by all accounts a rather happy one, and certainly a full one. Not only was his and Katharina’s house to become home to six children – Hans, Elisabeth (who died as an infant), Magdalena, Martin, Paul, and Margarethe – but they also played host to many boarders over the years, most of them students. Over meals, Luther would answer their questions on a wide variety of topics. Some of these statements were recorded in a document now known as the Tabletalk. Luther’s experiences with his own children helped to shape his ideas on the importance of education and may have been in the back of his mind as he wrote the Small and Large Catechisms.

Although it began as a rather scandalous pairing, Luther’s marriage with Katharina proved to be highly beneficial both for him and for Protestantism by providing an ideal of marriage. Although the Luthers certainly had their share of marital difficulties, Martin’s letters to his wife demonstrate the love between them. Particularly difficult was the death of their daughter Magdalena at age thirteen, the young lady dying in her father’s arms. Although we possess little of Katharina Luther’s own words, we do have this statement that she made following her husband’s death:

“If I had a principality or an empire I wouldn’t feel so bad about losing it as I feel now that our dear Lord God has taken this beloved and dear man from me and not only from me, but from the whole world. When I think about it, I can’t refrain from grief and crying either to read or to write, as God well knows.”[2]

Luther and Pastoral Care

Statue of Martin Luther in Dresden, Germany

Although he is often known for his theological works and even his hymns, Luther was also a pastor, and the concerns of pastoral ministry were to dominate much of his thought. As the years went by and the ideals of the Reformation began to be implemented more and more, the need for good pastoral care only increased. It was concern for his parishioners that largely motivated Luther’s decision to take a stand on the issue of indulgences. Already in 1519, he wrote the Sermon on Preparing to Die, a topic that was surely of importance to many in his congregation. His translation work can also be seen in the context of a more practical kind of theology: helping average Christians to understand scriptural truth in their own language.

Between 1528 and 1531, a visitation was carried out among the Protestant churches in Saxony, both by Luther and others. This revealed several problems that were occurring in the congregations that Luther subsequently aimed to address. In his position as a university professor and leader of the Protestant movement, Luther worked for many years to mentor those who would proclaim the Word of God. He also was not above publishing a pamphlet on prayer for his barber when the man asked him a question. This shows Luther’s concern for all of his congregants. Even things such as sex, which affected everyone but were not openly discussed by most theologians, were addressed by Luther in a very straightforward manner.

Luther’s Later Years

Less attention is typically given to the last 15 years of Luther’s life, by which point he had already written many of his most famous works. However, he was still very busy as both a pastor and professor, helping to reorganize the faculty and curriculum at the University of Wittenberg during the 1530s. In 1534, the full German translation of both the Old and New Testaments appeared in print. This translation continued to be revised, even after Luther’s death. Some of Luther’s pamphlets from this time, particularly regarding the Jews in Germany, proved to be very controversial due to their exceedingly harsh nature. Thus, Luther was not a perfect man, and some of the disappointments he experienced in his life undoubtedly added to his frustration.

Along with some of his comments during the Peasants’ War of 1524-25, Luther’s writings about the Jews have attracted much modern criticism. While not dismissing this criticism, we must consider the totality of Luther’s work, and that the very things that made him strong could also appear as weaknesses. Though imperfect, God was still able to use his passion for truth to do great things. He died on February 18, 1546 in Eisleben, the same town where he was born.

Martin Luther’s Legacy

Martin Luther is remembered as a passionate writer and preacher, an influential theologian, and a loving father, husband, and mentor. In everything he did, he maintained an intensity, dedication, and sense of humor that served him and the Protestant Reformation well. His early need for assurance and search for truth led him on a journey that would change the course of history. His life serves as an inspiration for all who seek to know God better.

[1] Quoted by Martin Brecht in Martin Luther: His road to Reformation, 1483-21. Translated by James Schaaf. Copyright 1985 by Fortress Press.

[2] Published in Martin Luthers Briefe, Sendschreiben und Bedenken, edited by Martin Leberecht de Wette and Johann Karl Seidemann, Volume 6 (Berlin: Reimer, 1856). Translation by Martin Treu.

Martin Luther is my inspiration after Jesus, what a personality hats off please pray all who read this autobiography, I want to do something for my people.